As Christians involve themselves – for good and for bad – in the divisive politics and cultural struggles of our nation, it is assumed they do so to preserve and advance a moral ethic consistent with Scripture.

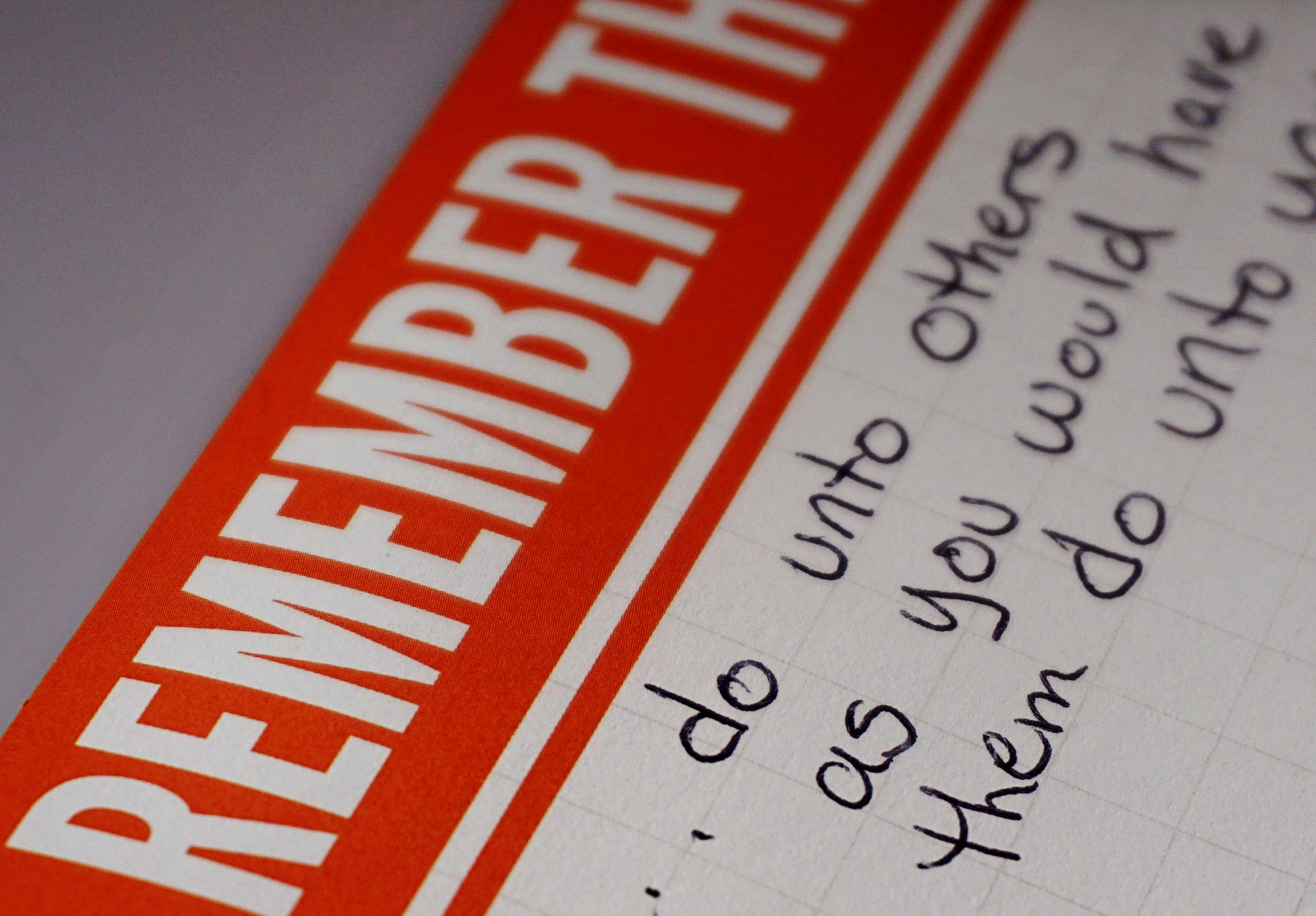

Unfortunately, it can be easy to forget one of the central marks of this morality: ‘Do unto others, as you would have others do unto you.’

This command, and it is necessary to remember it is an active imperative, concerns many issues of the day. I would submit that current Muslim-Christian relations illustrate this selective memory, and the Middle East provides a useful mirror.

In the Arab world it is Christians who are the great minority. How do they describe their situation? Much like in America, there is considerable nuance.

It must be said at the outset that the comparison will not be exact. The US enshrines religious freedom for the individual and forbids a religious test for public office. While these concepts are not absent from the Arab world, they are mixed in with many constitutions that enshrine Islam as the religion of the state and sharia law as the basis of legislation. At the official level these articles can complicate matters considerably.

But what about the popular level?

To be certain there is a spirit that, while tolerating Christianity, strives to preserve and advance the Islamization of society. Some conservative Muslims argue that Christians should not be greeted on their holidays, lest it imply endorsement of false theology. Others warn their children against playing with Christians at school. And many Christians complain of discrimination that is mixed in with a general culture of nepotism.

But Christians the region over also speak of neighborly relations with normal people who happen to be Muslims. Post-Arab spring, many Arab governments are going out of their way to combat extremism that has crept into society. And as reflected in my recent article “What Arab Christians think of the ‘Same God’ debate” (originally in Christianity Today, Jan 13, 2016), many Arab Christians are comfortable saying they and their fellow Muslim citizens worship the same God.

Yet the article also described an undercurrent of frustration, that Christians feel internally compelled to seek common theological ground in order to secure common societal acceptance. The more some push the distinctiveness of Christianity, the more they fear either government or popular response.

Within the diversity of these Arab responses there is also advice for America and the West: Limit the presence of Muslims in your midst. The complaint is not so much against Muslims as a people, but of Islam as a religion. The more devout the practice, they say, the greater the enthusiasm to enact its superiority – not just in the afterlife, but to bring this world into conformity as well. As evidence, they simply point to their own societies.

Whatever is made of the ‘same God’ debate, Islam and Christianity are different religions. But different also is the historical fusion between these religions and their respective societies.

It is good to learn from our Arab brothers and sisters in Christ about their experience with Islam where they are the minority. But the point here is not so much to arm with argument but to invite readers to flip the script and see within it a mirror to their own society.

How might American Muslims feel about our current social and political climate? Would they say most neighbors treat them well? Would they complain they have to accommodate their faith to a dominant culture? Would they state a concern over discrimination or a fear of rejection?

Many Arab Christians have responded to their challenges by withdrawing into their own communities. Are American Muslims tempted to do the same? And what of the warning some Arab Christians issue about Islam? How similar is it to some Muslim warnings about decadent Western society and the Christianity that is powerless to arrest it? Or, others argue, the Christianity that is in league with colonialism or Zionism or consumer capitalism to radically alter the fabric of Muslim society?

Let every charge be answered, and every religious ideology be examined. But let every American Christian return to the imperative of Christ: “Do unto others as you would have others do unto you.“

Consider the situation in which Middle Eastern Christians live and ask, how would you like this ‘you’ to be treated?

It is not argued that treating American Muslims well will necessarily make any difference to the Egyptian Copt, the Lebanese Maronite, or the Iraqi Assyrian. But any mistreatment of Western Muslims is often reported in the regional press, and gives fuel to those with an axe to grind.

The Golden Rule is not about quid pro quo. It is fulfillment of the law of Christ, who served those who loved him not. Please be mindful, for concerning Muslims it is often we who so rarely love.

One thought on “The Difficulty with “Do unto others””

Comments are closed.