Editorial Note: The following is a short introduction on early Gospel manuscripts and the origins of the name of Jesus in these Arabic texts from Dr. Hikmat Kashouh’s new book and study volume The Gospels In Arabic: The Gospel of Matthew published in Lebanon by Dar Manhal al Hayat, 2020.

Central to understanding the Arab Christian heritage are the Arabic versions of the Gospels. Though tangled and often confused, much can be gleaned from the language and history of these fascinating texts. For example, there is much scholarly debate on the origin and meaning of the name for Jesus used in Islam and the Qur’an to this day, which I will elaborate on below. This new volume is a comparative edition of the Gospel of Matthew in Arabic which represents thirteen different Arabic translations produced by our forefathers from as early as the sixth or seventh centuries until the thirteenth century AD. This volume is the first in a series of four volumes covering the Four Gospels.

The more I study these ancient texts the more I am convinced that the surviving manuscripts are but a mere fraction of what existed in the hands of our forefathers. What was lost is much greater than what has survived. The hope is, now that the manuscripts are transcribed and available to be studied and compared with other versions, that what remains can shed a better light on this rich tradition and lead to deeper historical and biblical understanding.

In this book, I provide some new insight on the origin of the Arabic Gospels. In working on codex Vat. Ar. 13 I argue with new data, for example, that its archetype is a very old text of a unique nature, produced outside Bilād al-Shām (Land of Syria), translated from Syriac, anytime between 500 and 620 A.D. This is much older than commonly thought, but there are many evidences. We know for example that Syriac Christians were intimately involved in translating key philosophical and theological works for Islamic rulers and scholars in the early days of Islam.

The term “عيسى” (‘Isa) is the Qur’anic name for Jesus. Scholars have been puzzled by the origin of the term ‘Isa, and have offered a number of unconvincing explanations. For a recent summary of these other explanations and the related contextualization and mission issues see Martin Accad’s excellent summary.

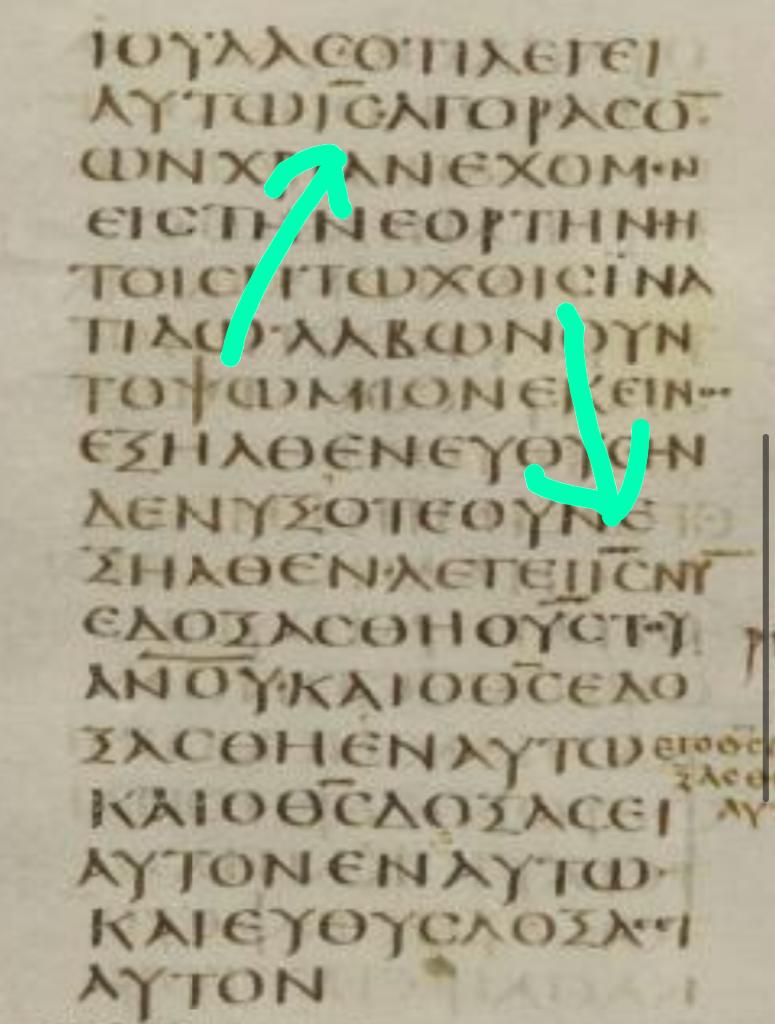

I would argue that ‘Isa simply comes from the Greek Ἰησοῦς (Iesous), written as a nomen sacrum (sacred name). This is not in the usual expanded way of today, but in a commonly abbreviated manner (i.e. “IC”) with a line over it, namely “IC”. This is a distinctive writing feature of sacred names in early Greek manuscripts. So, it is very likely that ‘Isa comes from the Greek sacred name IC (pronounced Ee-Sa), as “عيسو” comes from Ησαυ (Esau). Moreover, “عيسى” parallels “موسى” (Mūsa), like the well-known pairs of Ismā‘īl and Ibrāhīm, and Jālūt and Tālūt. Finally, one might entertain the idea that the fact that the Qur’anic tradition preferred “عيسى” for IC, instead of “يسوع” (Yessua) for Ἰησοῦς, could point to how this name was revered in the early Islamic era, and was indeed considered a nomen sacrum (The Gospels in Arabic, pp. 17-18, fn. 1.).

The book has an introduction of more than 200 pages followed by approximately 1,100 pages of the transcription of the verses from the various Arabic versions placed in parallel. This introduction includes some valuable information, descriptions, important guidelines, and an Arabic-English lexicon to assist the reader while reading the Gospel text. Now that the texts are transcribed, a linguistic and textual study has become accessible to all.

The purpose of this work is to place in the hand of Eastern and Western communities the Gospels in Arabic as they were read by our Eastern ancestors until the age of the printing press. Those familiar with the Arabic versions of the Gospels are aware of how little we know about this corpus. My hope is that the scholarly community will find this arrangement of primary source texts helpful in order to continue the journey of discovering the richness of the Arabic Christian heritage, through this biblical tradition. This work is an invitation to scholars, and to students of Arab Christianity and of editing texts in religion, to study these texts from a textual, liturgical, ecclesiological, theological, historical, linguistic, and social perspective.

You can find The Gospels in Arabic on Amazon.