Editor’s Note: Below is a summary of a PhD research project from the December 13 defense in Amsterdam: ‘Reshaping the Ultimate Other: Levantine Conversion from Extremist Islam to Christianity through the Lenses of Deradicalization and Missiology’. You can read the abstract here.

Through ethnography and life-story interviews with 52 very special people (about half former Islamic extremists and half religious workers), I explored a conversion phenomenon in Jordan, Syria, Lebanon and Iraq that began in 2011 as the refugee crisis escalated due to regional conflict. This phenomenon is widespread, with estimates of conversion in the tens of thousands. Though this point needs further research, and numbers are difficult to attain, this could well be the largest conversion phenomenon to Christianity since the 1st century in the Levant.

I sought to answer the question How we can understand the conversion phenomenon of extremist Muslims to Christianity in the Levant? I explored 1.) the historical context 2.) the major themes emerging, then I looked at the phenomenon through two lenses: 3.) deradicalization and 4.) missiology.

When I have discussed my work with friends and neighbors, I often get puzzled looks and a set of questions such as, “You spoke with Islamic extremists? and you actually went to the Middle East… aren’t they all terrorists? and wait…extremists converted to Christianity?” I am keenly aware of my own positionality as a White Christian American, the checkered history of evangelical engagement in the Middle East and the very political nature of conversion, mission and deradicalization. Nonetheless, I endeavored to listen and paint the contours of this fascinating phenomenon.

Historical Context and the Conversion Pattern

First, we observe historically that the Levant is no stranger to precarity, sectarian violence, and extremism. The themes of millenarianism, the supernatural and patterns of conversion appear through various time periods. But we also observe small alternative Christian communities in each time period living counter to these power currents such as the Antioch church in the first century, Nestorian monasticism during the Islamic era, Franciscans during the crusader era, and Presbyterians and Baptists following the World Wars. Levantine evangelicals followed a historical counter-cultural thread when they served refugees.

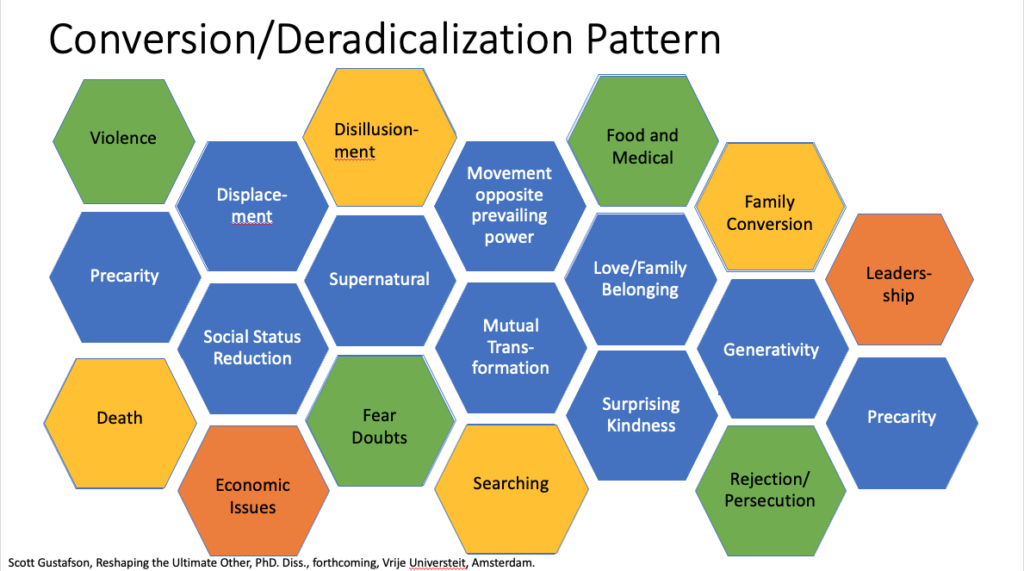

Secondly, these stories illustrate a common pattern, as interviewees walked a pathway over a period several years. Precarity emerged with killing, kidnapping, bombings, fear and trauma. Then there are supernatural visions, doubts and searching, movement against societal, political and familial power flows, the surprising kindness of perceived ‘enemies,’ mutual transformation of both extremists and clergy and the discovery of love and family belonging in new, alternative communities. Their stories are deeply moving, a humbling insight into the human experience of suffering, change and resilience.

I wish I had time to tell you all their stories… Nour for example shed tears as she recounted how she lost her entire family in one afternoon, watching planes bomb her house as IS fighters fired weapons from the roof. A pastor emotionally expressed deep regret at his hatred of Syrians and passionate empathy for their suffering now.

We see elements in these stories of many different theories and models. It is difficult to say where deconversion, deradicalization and conversion begin and end. Through the lenses of the interdisciplinary fields of deradicalization and missiology we see cognitive openings due to trauma, group dynamics, social attachments, issues of identity and belonging, network recruitment, re-pluralization, desistance from violence and elements common in religious conversion such as encapsulation. In all these macro, meso and micro factors, seen from various angles, a mysterious metanoiaic change unfolded involving belonging, behavior and beliefs.

“Left-Handed Power”

We also see the Levantine church theologizing, taken up with the Missio Dei offering and living out a compelling narrative of hope and cosmic restoration. Levantine Christians carried out their mission with a holistic pattern of acts of kindness, invitation, affective wooing and persuasion into the love of God.

Their hope is eloquently expressed in a 6th century advent hymn traditionally sung at Vespers this time of year titled “O Savior of Our Fallen Race.” Here are a few lines from this ancient hopeful chant that echoes in the Levantine church today:

From the Father’s throne You came,

His banished children to reclaim;

And earth and sea and sky revere

The love of Him who sent You here.

And we are jubilant today,

For You have washed our guilt away.O Savior of our fallen race,

The world will see Your radiant face

For You who came to us before

Will come again and all restore.

Now we rightly ask, what relevance is there to the traumatic stories of dislocated refugees, social theories, deradicalization, Ancient hymns, theology/missiology, and the religious conversion of some in the Levant?

In our world wracked with violence, polarization and extremisms of many forms this research illustrates counter-intuitive forces at our disposal both for deradicalization and for Christian mission. Humans have immense power to induce metanoia, to persuade others to turn away and turn towards ways of life consistent with human flourishing. While common to hear the term ‘soft methods’ in counter-terrorism, these more gentle methods may well be the most potent power at human disposal. Robert Capon describes much of Jesus’ way of life and his teaching as a demonstration of “left-handed power.”

While the right-handed might of direct force, revenge and retaliation, often seem like necessary choices, the long arc of relationship cultivation, empathy, surprising and perhaps undeserved kindness, love and community formation in the context of this study, proves itself efficacious both for deradicalization and for Christian mission.

Alternative Communities, Mutuality, and Holistic Care

First, fostering heterogenous alternative communities in hostile environments poses a powerful antidote to the us/them narrow binary that can lead extremists to question their tightly defined realities. This study and other similar research indicate some promise in stimulating strategic, deliberate cross-group contact and relationships between groups at odds. Empowering communities, like this study found in Levantine churches, is a compelling consideration to counter extremism. To be clear, I am not suggesting that conversion to Christianity is the only solution to the problem of Islamic extremism and radicalization. As a missiologist I am of course interested, however, extremists deradicalize through similar processes towards moderate Islam or atheism. These stories suggest that space for mutual persuasion, alternative communities and relationships are key ingredients.

A second implication is that agents willing to be mutually transformed and consider their own roles in creating conditions for extremism resist the mutual radicalization phenomenon. This ingredient of mutual transformation (of extremist and clergy) in the process is a key finding. While this study did not venture far into the areas of state and government influence, as a bonus thought, I wonder what transformative effects it might have if public actors disavowed actions that inflame radicalization?

Lastly I highlight the idea of holism. In a time where Western Mission especially seems so focused on church growth methods and counter terrorism efforts default to militaristic retaliation, the Levantine church invites us to see beyond the ‘target’ and enemy combatant motifs to the needs of the whole person. Visitation and hospitality created a sub-text, a mood that communicated love, belonging and invitation touching on the physical, social, spiritual. The shared table was a social expression of desire for relationship. Ironically it became, in a sense, a communion sacrament outside church walls, where bread and cup were shared, warring enemies made peace. It was a place of shared confession and mutuality where moral circles enlarged.

Extremists responded positively to the patient kindness and holistic care offered from an enemy out group. A pastor who has worked with many extremists said, “I tell you, they are not able to stand in the face of love.” A former extremist echoed, “We never experienced a love like this.” In short, it behooves both the fields of deradicalization and missiology to regard extremists as human beings, with feelings, desires and dreams. We might bravely imagine a different scenario in the Holy Land, for example, if people on all sides apprehended the full humanity and needs of the other.

To conclude, Levantine Christians together with former extremists, mutually transformed, have offered us a fascinating laboratory to explore the personal and societal effects of the kind of left-handed alternative communities even in a hostile environment. Their stories challenge us to recognize that there are many forces at work, from historical, psychological, social, theological and even perhaps supernatural, influencing us, shaping and curating our desires and loves. They challenge us to contemplate the power of love and how empowering alternative communities in hostile environments can re-shape even the ultimate other.